Attachment Theory and Addiction: How Attachment Shapes the Path Into and Out of Addictive Patterns

Introduction

Understanding attachment style and addiction together offers a compassionate and accurate way to understand why people turn to substances or compulsive behaviors. Rather than viewing addiction as a lack of willpower, attachment theory and addiction research suggest that addictive patterns often develop when early relationships lack safety, emotional regulation, or predictable support. As John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth, and Dan Siegel show, our attachment patterns shape how we cope with stress, seek comfort, and regulate emotions.

When early needs are unmet or inconsistent, individuals often turn to substances or behaviors as substitutes for connection or soothing. Looking at addictions from an attachment perspective reveals that addiction is frequently an attempt to regulate attachment wounds, not a personal weakness.

What Is Addiction?

Addiction is a compulsive pattern of using substances or behaviors even when they create harm. Although addiction affects the brain and nervous system, it is also an emotional regulation strategy. People often use substances to ease loneliness, numb emotional pain, escape stress, or create a temporary sense of control.

Experts such as G. Alan Marlatt and Philip J. Flores describe addiction as a progression that begins long before substances appear. It begins with chronic emotional dysregulation, relational disconnection, or unresolved distress. Through the lens of attachment theory and addiction research, addictive behavior becomes understandable as an attempt to self-soothe when secure relationships were not available.

Autoregulation and Co-Regulation in Addiction

Attachment theory and addiction intersect most clearly in the concepts of co-regulation and autoregulation. In secure early development, children learn to settle their nervous system through co-regulation. A caregiver offers warmth, comfort, and steady presence, and over time these experiences become internalized as healthy self-regulation.

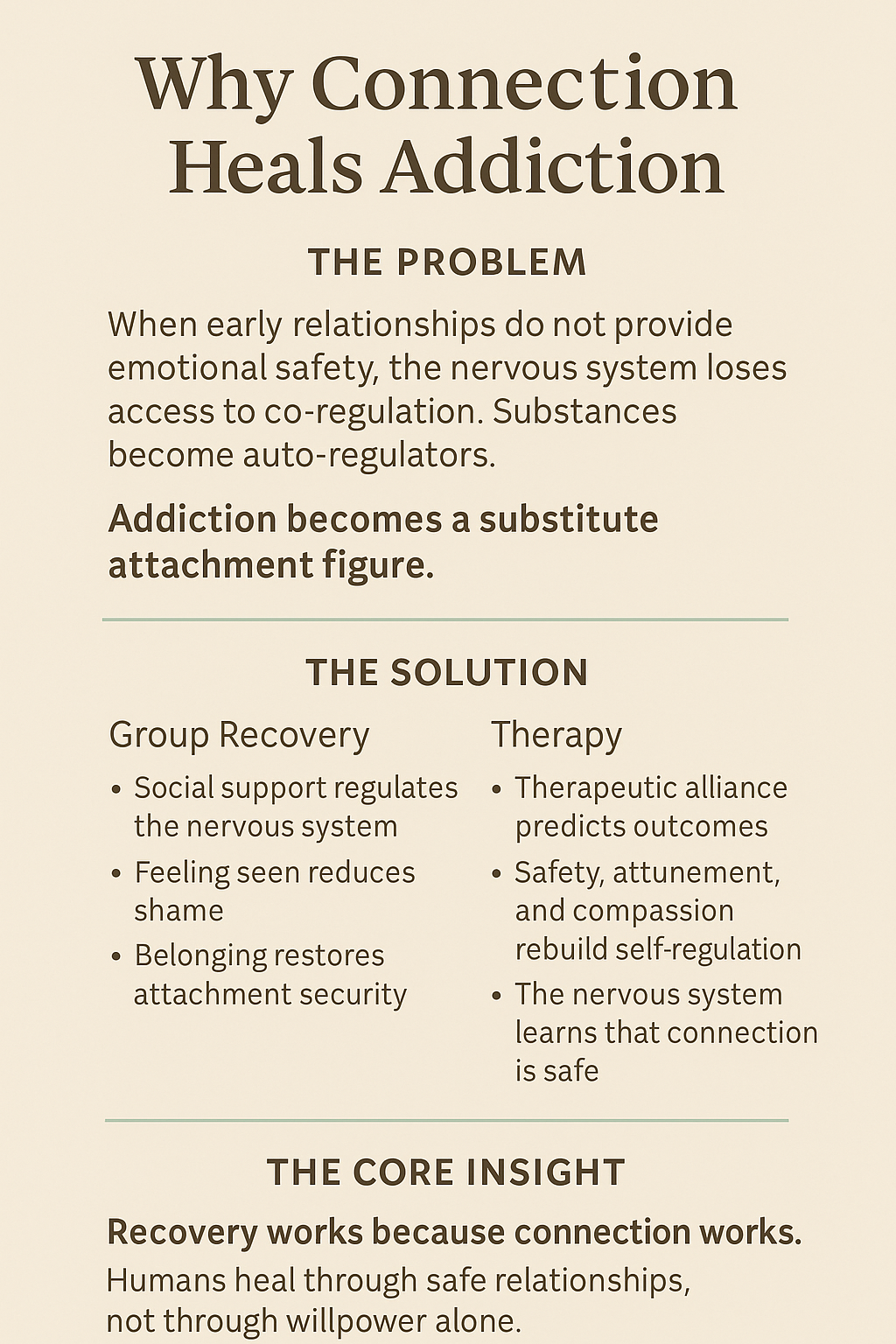

When early caregiving is inconsistent, frightening, or absent, the child does not receive reliable co-regulation. The nervous system must rely on autoregulation strategies that do not involve connection. These strategies become default coping mechanisms in adulthood.

Substance and process addictions are auto-regulatory in nature. Substances and behaviors create predictable relief when co-regulation is unavailable. Alcohol may soften fear. Opioids may create comfort. Stimulants may manage focus or internal chaos. Gambling, sex, food, and work addiction offer temporary control or escape.

From an attachment and addiction perspective, addiction functions as a substitute attachment figure. Substances offer predictable soothing that early relationships did not provide.

This insight helps explain why addiction feels so compelling. It fills a relational void. Yet because autoregulation cannot replace genuine connection, addiction eventually deepens isolation and dysregulation.

Why Connection Heals: The Social Cure in Addiction Recovery

Understanding autoregulation and co-regulation helps clarify why connection is the strongest healing force in addiction recovery. Many people assume recovery groups are effective because of program steps or specific content. However, from an attachment style and addiction perspective, the central benefit of these groups arises from the consistent co-regulation found in community.

When individuals gather in a supportive group, their nervous systems receive the relational nourishment that may have been missing in early life. Being witnessed, accepted, and understood reduces shame and increases emotional stability. Support groups reintroduce the co-regulation that addiction attempted to replace.

Therapeutic Alliance as Co-Regulation

This same principle explains why psychotherapy works. Decades of data show that the strongest predictor of healing is the therapeutic alliance, not the specific modality. In attachment theory and addiction treatment, the alliance is essentially a co-regulatory relationship.

Clients heal when they experience emotional safety, compassion, attunement, and the sense of being known. The therapist becomes a consistent, predictable source of regulation until the client internalizes these capacities. In this secure functioning relationship, the nervous system learns to trust connection again.

Why This Matters for Addiction Recovery

People do not recover in isolation. Recovery requires relationships that offer stability, predictability, and emotional presence. When individuals feel safe, seen, and supported, their reliance on substances decreases. Co-regulation helps reorganize the attachment system, making sobriety more sustainable.

In summary, recovery works because connection works. It restores the secure relational foundation that addiction temporarily imitated.

Attachment Theory and Addiction

With this foundation, the connection between attachment theory and addiction becomes clearer. When early caregiving does not offer reliable emotional safety, the nervous system must cope alone. Substances become a predictable replacement for co-regulation.

This is why many clinicians describe addiction as an attachment disorder. Understanding addiction attachment patterns through the lens of attachment style reveals what each individual needs in order to heal. Recovery requires addressing both the behavior and the attachment system that shaped it.

Attachment Styles and Addiction

Anxious Attachment and Addiction

Individuals with an anxious attachment style tend to experience heightened emotional intensity, fear of abandonment, and chronic uncertainty about whether their needs will be met. Early caregiving was often inconsistent, sometimes responsive, sometimes unavailable, leading the nervous system to remain in a state of hyperactivation. As adults, these individuals may feel easily overwhelmed by loneliness, rejection, or relational conflict. Addiction can emerge as an attempt to regulate this emotional flooding. Substances such as alcohol, stimulants, or sedatives may temporarily reduce anxiety, provide comfort, or create a sense of connection and relief from panic. Compulsive relational patterns, including love addiction or codependency, can serve a similar function.

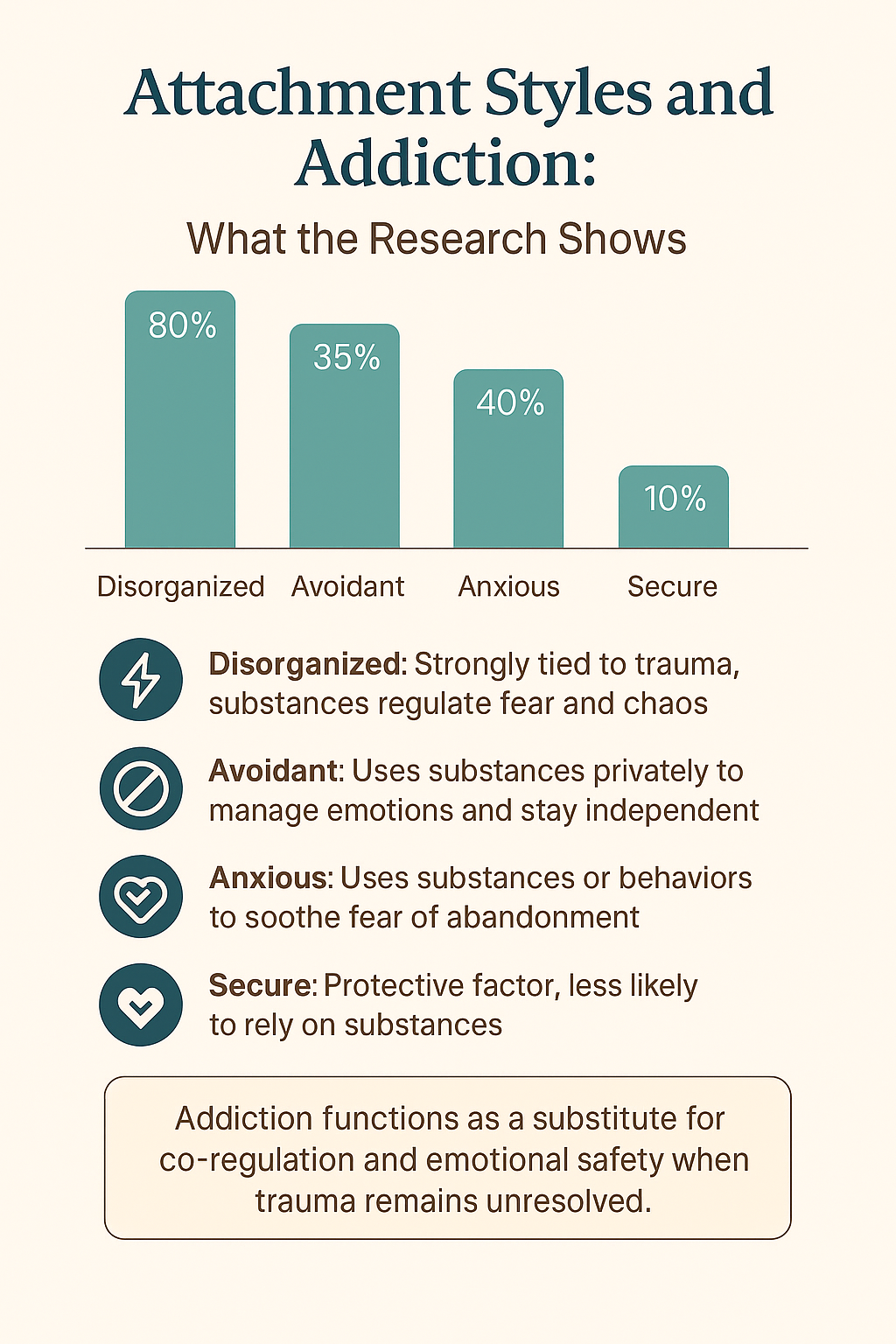

Research shows that anxious attachment is present in approximately 20–40% of individuals with substance use disorders. From an attachment-based perspective, addiction substitutes for the predictable soothing that early relationships failed to provide. Effective treatment focuses on building consistent, reliable support, strengthening emotional regulation skills, and helping individuals tolerate separation, uncertainty, and distress without resorting to substances.

Avoidant Attachment and Addiction

Avoidantly attached individuals learned early that emotional needs were ignored, dismissed, or met with discomfort by caregivers. As a result, they adapted by minimizing vulnerability, suppressing emotional awareness, and relying heavily on self-sufficiency. While this strategy may appear functional on the surface, it often disconnects individuals from their internal emotional states. Addiction can develop as a private and controlled means of managing stress, numbing discomfort, or maintaining emotional distance from others. Substances may help avoidant individuals shut down feelings, reduce dependency needs, and preserve a sense of autonomy.

Studies estimate that approximately 30–35% of individuals with addiction exhibit avoidant attachment patterns. Because these individuals often do not seek help easily, addiction may progress quietly and remain hidden for long periods. In recovery, avoidantly attached individuals benefit from gradual exposure to relational safety, increased emotional awareness, and non-intrusive support. Treatment emphasizes respecting autonomy while gently introducing co-regulation and helping individuals reconnect with emotions without feeling overwhelmed or engulfed.

Disorganized Attachment and Addiction

Disorganized attachment develops when caregivers are experienced as both a source of comfort and a source of fear, often due to abuse, neglect, or unresolved trauma. This creates a profound conflict within the nervous system: the person simultaneously seeks and fears closeness. Without a consistent strategy for emotional regulation, the individual may experience intense internal chaos, dissociation, or sudden emotional shifts. Addiction often becomes a powerful attempt to manage this instability. Substances may numb terror, reduce overwhelming arousal, or provide temporary relief from fragmented inner states.

Disorganized attachment shows the strongest association with addiction, appearing in up to 80% of individuals in severe addiction treatment settings. From an attachment lens, substance use functions as an external regulator for a nervous system that never developed reliable internal regulation. Recovery requires trauma-informed, attachment-focused care that prioritizes safety, predictability, and stabilization. Long-term healing involves rebuilding trust in relationships, integrating traumatic experiences, and developing new regulation capacities within a consistent therapeutic relationship.

Secure Attachment and Addiction

Secure attachment acts as a protective factor against addiction because it supports emotional regulation, self-reflection, and help-seeking behavior. Securely attached individuals generally experienced caregivers who were responsive, predictable, and emotionally available. As a result, they develop confidence in relationships and the ability to manage distress without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down. Secure individuals are more likely to use social support, communicate needs effectively, and tolerate emotional discomfort during stressful periods.

Secure attachment is found in only less than 10 percent of addiction populations, compared to over 50% in the general population. When securely attached individuals do develop addiction, often due to environmental stressors, genetic vulnerability, or trauma later in life, recovery is typically more straightforward. They are more able to acknowledge the problem, engage in treatment, and accept support without excessive shame or fear. Strengthening secure attachment qualities within treatment can significantly improve recovery outcomes across all attachment styles.

Addiction as an Attachment Disorder

Philip J. Flores writes that addiction can be understood as an attachment disorder, rooted in early disruptions to safety and connection. When relationships do not feel reliable or emotionally safe, the individual often turns to substances for comfort, predictability, or relief from distress. Many people describe alcohol or drugs as companions, regulators, or even substitutes for care, something that is always available and never rejecting.

This reflects a core attachment pattern: substances temporarily replace co-regulation by soothing the nervous system when human connection feels threatening or unavailable. Healing therefore requires rebuilding emotional and relational safety, developing internal regulation skills, and restoring trust in supportive relationships over time.

Treatment for Addiction and Attachment Style

Lasting recovery requires more than behavioral change or symptom management. It involves healing underlying attachment wounds, restoring nervous system regulation, and developing the capacity for safe connection. Attachment-focused therapy, somatic trauma work, Ideal Parent Figure imagery, Emotionally Focused Therapy, mindfulness practices, and intentional relational repair all support the development of secure functioning. These approaches help individuals internalize safety, regulate affect, and replace substances with reliable internal and relational resources.

Each attachment style benefits from a tailored therapeutic approach. Anxiously attached clients need predictability, emotional stability, and reassurance that needs can be met without escalation. Avoidantly attached clients require respect for autonomy alongside gradual support in tolerating vulnerability and emotional awareness. Disorganized clients need trauma-informed care, nervous system stabilization, and consistent attunement to repair fragmented attachment strategies.

When addiction is understood through attachment theory and addiction research, recovery becomes not just abstinence, but a profound relational and developmental transformation.

Conclusion

When seen through attachment theory, addiction becomes understandable as an attempt to regulate emotions that were never co-regulated in early life. Substances serve as auto-regulatory strategies that temporarily replace missing comfort.

Recovery involves restoring the capacity for safe connection. It is a process of developing secure attachment, strengthening emotional resilience, and learning to regulate emotions both internally and with others. With the right support, long-standing patterns can transform, allowing individuals to create a more grounded and connected life.

References and Influences

The ideas in this article are informed by leading researchers and clinicians in attachment theory, addiction, trauma, and interpersonal neurobiology.

Attachment Theory

John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth: Foundational attachment research.

Dan Siegel: Interpersonal neurobiology, co-regulation, and self-regulation.

Mary Main and Erik Hesse: Adult Attachment Interview and disorganized attachment.

Attachment and Addiction

Philip J. Flores: Addiction as an Attachment Disorder.

Armin Schindler: Insecure and disorganized attachment in substance use disorders.

Thorberg & Lyvers: Attachment patterns in alcohol misuse.

De Rick & Vanheule: High prevalence of disorganized attachment in inpatient addiction treatment.

Trauma and Nervous System Regulation

Stephen Porges: Polyvagal Theory and the biology of safety

Peter Levine: Somatic approaches to trauma and regulation.

Bessel van der Kolk: Trauma, memory, and relational healing.

Attachment-Focused Clinical Models

Daniel P. Brown and David Elliott: Ideal Parent Figure and Integrative Attachment Therapy.

Sue Johnson: Emotionally Focused Therapy and secure bonding.

Stan Tatkin: Secure-functioning relationships in couple therapy.

Patricia Crittenden: Dynamic-Maturational Model of attachment.

Group Healing and Recovery

G. Alan Marlatt: Relapse prevention and emotional regulation.

Bruce Alexander: Social connection and addiction (Rat Park).