Understanding Trauma and Addiction: How Unresolved Trauma Shapes Substance Use and Recovery

Introduction

The relationship between trauma and addiction is powerful, consistent, and well-documented. Research shows that up to 80 percent of people in substance use treatment have a history of significant trauma, and many are living with symptoms that were never fully seen, supported, or regulated. Trauma overwhelms the nervous system, disrupts emotional regulation, and changes how a person experiences their body, relationships, and the world. Addiction then becomes a way to cope with this internal chaos.

Understanding the connection between addiction and trauma helps us see addictive behaviors not as failures but as adaptations. Substances and compulsive behaviors often emerge as survival strategies when support, safety, or co-regulation were missing. Trauma-informed addiction treatment is rooted in compassion: the recognition that pain, rather than pathology, drives addiction.

What Is Trauma?

Trauma is not defined by the event itself, but by the impact the event has on the brain and nervous system. As Bessel van der Kolk explains, trauma is “an experience that overwhelms your capacity to cope.” Trauma leaves the nervous system stuck in patterns of hyperarousal, collapse, fear, or numbness.

Dan Siegel describes trauma as a rupture in integration: the mind and body lose their ability to stay regulated. Without support to process the experience, the system becomes fragmented. This is why so many people turn to substances. The relief may be temporary, but it offers a momentary sense of control, escape, or calm.

In this way, trauma and addiction connection is rooted in the nervous system, not in morality or willpower.

Big T and Little t Trauma: Understanding the Full Spectrum

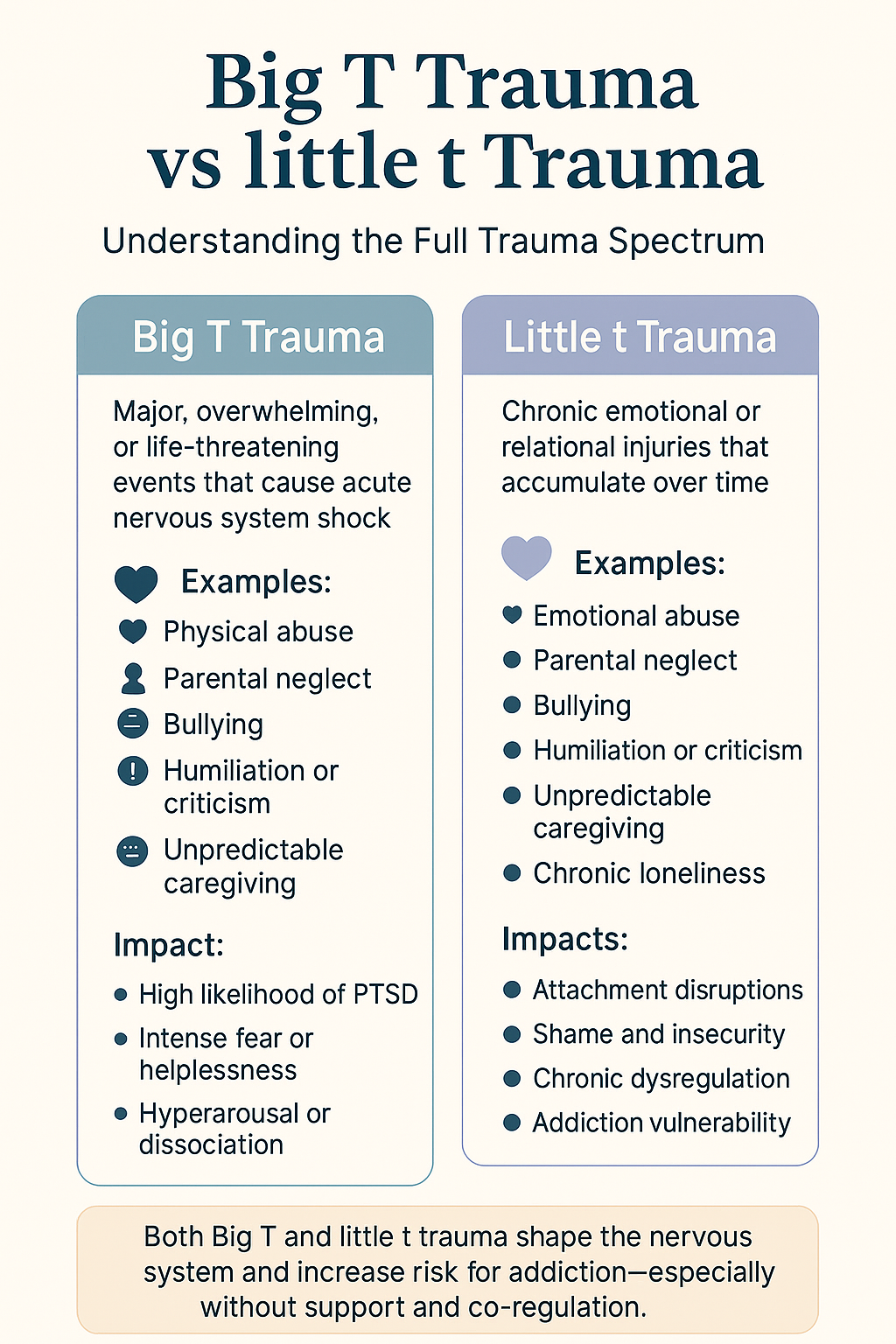

Trauma does not only come from extreme events. Clinicians often distinguish between Big T Trauma and little t trauma to describe the full range of experiences that can overwhelm the nervous system.

Big T Trauma refers to acute, life-threatening, or catastrophic events such as physical assault, sexual assault, major accidents, natural disasters, or medical emergencies. These events are sudden, shocking, and often leave clear PTSD symptoms.

Little t trauma, on the other hand, refers to chronic, relational, or emotional injuries such as neglect, criticism, bullying, humiliation, inconsistency in caregiving, or growing up in an emotionally unsafe environment. These experiences may appear “small” from the outside, but their accumulated impact on attachment, regulation, and identity can be profound.

Both types of trauma alter the nervous system and significantly increase vulnerability to addiction, especially when support and co-regulation are absent.

Big T Trauma vs. Little t Trauma

This visual illustrates the full spectrum of trauma and how both acute, overwhelming events (Big T trauma) and chronic, relational injuries (little t trauma) shape the nervous system. Big T trauma includes life-threatening or highly overwhelming experiences that often lead to PTSD, intense fear, hyperarousal, or dissociation. Little t trauma reflects ongoing emotional injuries such as neglect, criticism, or unpredictable caregiving that accumulate over time and disrupt attachment, emotional regulation, and self-worth. While different in form, both types of trauma increase vulnerability to addiction by impairing co-regulation and internal stability, especially when early support is absent.

Types of Trauma

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse is one of the most underestimated yet impactful forms of trauma. It includes criticism, shaming, humiliation, manipulation, or chronic invalidation. Unlike physical harm, emotional abuse targets a person’s sense of worth and identity. When a child repeatedly receives messages that their feelings do not matter or that they are “too much,” “not enough,” or fundamentally flawed, the nervous system adapts through shame, hypervigilance, or self-protective withdrawal. Over time, emotional abuse shapes how a person relates to themselves and others. It disrupts attachment security, undermines self-regulation, and increases vulnerability to addiction. Many people turn to substances to numb internalized shame or manage the emotional instability caused by years of psychological harm.

Parental Neglect

Parental neglect is a profound form of developmental trauma. It occurs when caregivers are emotionally or physically unavailable, inconsistent, overwhelmed, or unable to provide attuned care. Children depend on co-regulation—comfort, soothing, presence—to build the neural pathways for self-regulation. When that support is missing, the child’s nervous system becomes chronically dysregulated. Neglect is strongly linked to childhood trauma and addiction because it creates a void where safety and emotional connection should exist. In adulthood, substances may become substitutes for the comfort that was never consistently offered. Alcohol may soften loneliness, opioids may mimic a sense of warmth, and stimulants may counteract collapse or dissociation rooted in early unmet needs.

Bullying

Bullying is a relational trauma characterized by repeated intimidation, humiliation, exclusion, or aggression. It often occurs during critical developmental periods when identity and self-esteem are still forming. Bullying creates chronic fear and insecurity, leading the nervous system to stay on high alert. Victims may internalize shame, believe they are unworthy of connection, or learn to mask their emotional pain. Without supportive relationships to counteract the harm, the impact of bullying can follow a person into adulthood. Many people who experience prolonged bullying use substances or dissociative behaviors to escape intrusive memories, social anxiety, or the emotional wounds left by peer rejection. Bullying is one of the most common precursors to anxiety, depression, and addiction.

Physical Assault

Physical assault overwhelms the body’s built-in safety system. When someone experiences violence or the threat of physical harm, the nervous system shifts instantly into survival mode. Fight, flight, or freeze responses may activate so strongly that the body becomes conditioned to anticipate danger long after the event ends. Physical assault often leads to hypervigilance, intrusive memories, rage, dissociation, or difficulty trusting others. These symptoms can feel unbearable without support, making addiction more likely. Substances may temporarily numb pain, reduce fear, or create a false sense of control. Over time, this coping strategy can evolve into dependency, especially if the trauma remains unprocessed. Healing requires restoring safety, grounding, and body-based regulation.

Sexual Assault

Sexual assault is one of the most profound violations of bodily autonomy and psychological safety. It often leads to intense shame, fear, self-blame, and disruptions in one’s sense of identity. Because sexual trauma affects both the body and relationship systems, survivors frequently struggle with intimacy, boundaries, trust, and emotional regulation. The nervous system may oscillate between hyperarousal and numbing, making ordinary life feel overwhelming. Addiction can emerge when substances become tools for coping with intrusive memories, dissociation, anxiety, or pain. Survivors may use alcohol, opioids, or stimulants to suppress overwhelming emotions or reclaim a sense of control. Healing requires trauma-informed care, compassion, attunement, and a slow rebuilding of safety within the body and relationships.

Accidents

Accidents such as car crashes, falls, or sudden injuries can shock the nervous system and create lasting patterns of hyperarousal. Even when the body heals, the mind may remain stuck in the moment of fear or helplessness. Many people develop somatic symptoms, panic, or avoidance behaviors that interfere with daily life. Accidents can also lead to chronic pain, medical procedures, or long-term physical challenges, which increase vulnerability to addiction. Pain medications may become a primary source of relief, emotionally or physically. Without adequate trauma support, individuals may rely on substances to manage fear, numb discomfort, or escape traumatic memories. Recovery involves body-based therapies, grounding, and restoring a sense of physical safety.

Illness

Serious or chronic illness can be deeply traumatic. Medical trauma often includes fear, uncertainty, invasive procedures, hospitalization, or long-term physical limitations. Illness disrupts a person’s sense of control, safety, and identity. It can create feelings of helplessness, isolation, and exhaustion. Chronic pain or discomfort may keep the nervous system in a prolonged state of stress. As a result, individuals may turn to substances—especially pain medications, sedatives, or alcohol—to cope with both physical suffering and emotional overwhelm. Illness-related trauma is strongly associated with anxiety, depression, and addiction. Healing requires compassionate care, nervous system regulation, community support, and rebuilding trust in one’s body.

Signs of Trauma

Physical Signs

Hypervigilance or constant tension

Sleep disturbances

Fatigue or chronic pain

Digestive problems

Headaches or migraines

Startle response

Behavioral & Emotional Signs

Avoidance or emotional numbing

Irritability or anger

Substance use or compulsive behaviors

Difficulty trusting others

Flashbacks or intrusive memories

Difficulty concentrating

Feeling unsafe, disconnected, or unreal

The Link Between Trauma and Addiction

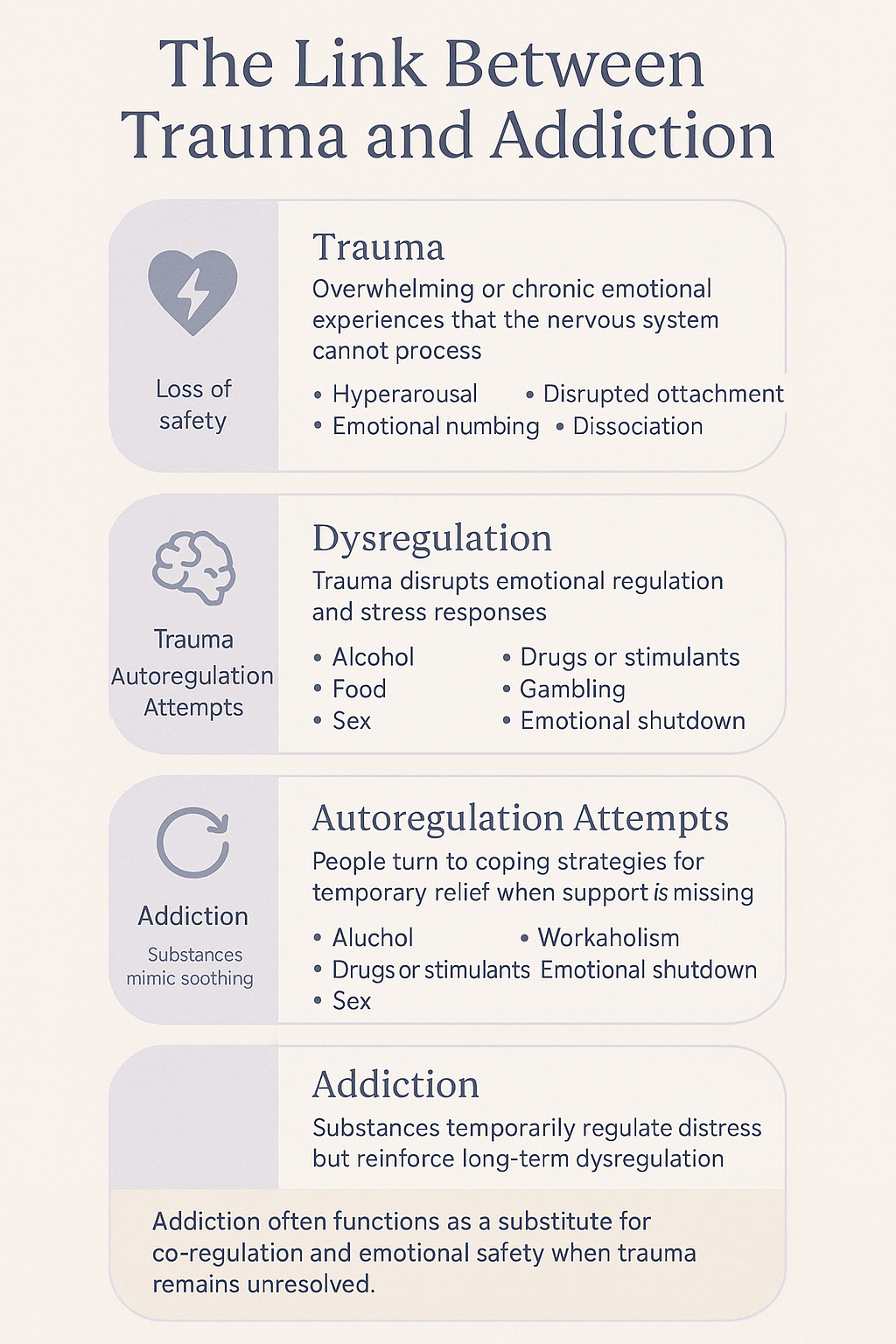

The relationship between trauma and addiction is rooted in the nervous system. Trauma disrupts emotional regulation, increases stress hormones, and impairs the brain’s reward and attachment circuits. Substances create temporary relief by numbing pain, activating reward pathways, or calming hyperarousal.

Bruce Perry, Stephen Porges, and Peter Levine all emphasize that unresolved trauma leads to dysregulation. Addiction becomes an auto-regulatory strategy. It provides momentary stability when a person cannot find safety in themselves or others.

In fact, the ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study found that individuals with high trauma scores are 4,600% more likely to develop substance use disorders.

This is why the link between childhood trauma and addiction is one of the strongest findings in mental health research.

The Link Between Trauma and Addiction

This visual illustrates how unresolved trauma leads to addiction through nervous system dysregulation. Trauma overwhelms the system and disrupts emotional regulation, attachment, and a sense of safety. In the absence of co-regulation and support, individuals turn to substances or compulsive behaviors as attempts at self-soothing. While these strategies provide temporary relief, they reinforce long-term dysregulation and dependence. Addiction, in this framework, functions as a substitute for emotional safety and co-regulation when trauma remains unprocessed.

Early Childhood Trauma and Addiction

Childhood trauma is the strongest predictor of adult addiction. Trauma during early development shapes brain architecture, attachment patterns, and stress physiology. Children who grow up with neglect, emotional abandonment, domestic violence, or unpredictable caregiving do not receive the co-regulation necessary for healthy nervous system development. Their stress systems remain chronically activated or shut down, impairing emotional integration and self-soothing capacity.

As a result, these children often develop:

hyperarousal or vigilance

dissociation

chronic anxiety

emotional numbness

insecure attachment patterns

Without early emotional support, the child learns to regulate alone. In adulthood, substances become a substitute for connection. Alcohol may quiet panic. Opiates may soothe attachment wounds. Stimulants may counteract dissociation or collapse. This is why addiction and childhood trauma are so consistently linked. Healing must address both the trauma and the attachment system that developed around it.

PTSD and Addiction

People with PTSD frequently turn to substances to manage intrusive memories, fear states, and emotional overwhelm. Alcohol may be used to calm hyperarousal. Cannabis or sedatives may dull intrusive thoughts. Stimulants may be used to counteract numbness or dissociation. Over time, substance use can become the primary coping strategy when internal regulation feels impossible or unsafe.

PTSD also disrupts the prefrontal cortex (reasoning), amygdala (fear), and hippocampus (memory). This neurobiological disruption impairs threat assessment, emotional modulation, and narrative integration of experience, making emotional regulation extremely difficult. The cycle becomes self-reinforcing:

trauma symptoms increase substance use

substance use worsens trauma symptoms

shame and avoidance deepen both

This is why integrating PTSD treatment with addiction treatment is essential. Trauma and addiction recovery must happen together, not in isolation, and within relationships that support safety, regulation, and meaning-making.

Unresolved Trauma, Attachment Style, and Vulnerability to Addiction

Not everyone who experiences overwhelming or frightening events develops long-term trauma symptoms or addiction. The difference often lies in the attachment system and a person’s ability to process, integrate, and recover from stress. Attachment shapes the nervous system’s capacity to regulate emotion, seek support, and resolve difficult experiences. This is why the relationship between trauma and addiction is so strongly mediated by attachment patterns.

Insecure Attachment as a Risk Factor for Trauma and Addiction

Individuals with insecure attachment, especially those with disorganized attachment, are significantly more vulnerable to experiencing trauma and struggling to process it. Research shows that disorganized attachment is associated with:

higher rates of childhood trauma and neglect

increased exposure to unsafe or chaotic environments

difficulty interpreting danger cues accurately

limited ability to self-regulate during stressful events

reduced likelihood of seeking help or co-regulation

greater risk of developing dissociation and identity fragmentation

Because their early caregivers were frightening, inconsistent, or unavailable, disorganized individuals grow up without a coherent strategy for dealing with stress. The nervous system remains in a chronic state of dysregulation. When trauma occurs, it often stays unresolved, meaning the body continues to store the experience rather than integrating it.

Unresolved trauma creates intense emotional, somatic, and relational symptoms, which can resemble Axis II personality disorder traits such as:

emotional instability

impulsivity

chronic emptinessdissociation

unstable relationships

identity diffusion

For many, addiction becomes a way to manage these overwhelming internal states, making the link between trauma and addiction especially strong in individuals with disorganized attachment histories.

Why Secure Attachment Is a Protective Factor

Securely attached individuals are not immune to trauma. They can experience intense, life-threatening, or overwhelming events just like anyone else. The difference is that secure attachment gives the nervous system a way to return to safety.

Secure individuals typically have:

strong emotional regulation skills

the ability to seek and accept support

flexible coping strategies

trust in relationships

resilience during stress

coherent internal narratives

These capacities act as protective factors. Even when they experience trauma, their nervous system is more likely to process the event, integrate the memory, and move toward recovery. Support from loved ones, stable relationships, and healthy co-regulation significantly reduces the risk of PTSD, addiction, or chronic dissociation.

In other words, attachment style influences not just the risk of trauma, but the outcome of trauma. Secure people tend to metabolize traumatic stress, while insecure or disorganized individuals are more likely to remain stuck in unresolved trauma states.

Why Unresolved Trauma Leads to Addiction

When trauma is unresolved, the nervous system becomes overwhelmed by fear, shame, numbness, or internal chaos. Without secure attachment or emotional support, individuals turn to substances or compulsive behaviors to self-regulate.

This explains why:

80 percent of individuals in addiction treatment report significant early trauma.

Disorganized attachment is the strongest predictor of severe addiction.

Emotional neglect is one of the highest ACE predictors of drug addiction.

Addiction becomes a substitute for the safety, attunement, and co-regulation that were missing early in life.

Physical Trauma and Addiction

Physical injuries, chronic pain, or medical trauma often lead to dependence on pain medication. When pain becomes fused with emotional trauma, substances are used not only for physical relief but for emotional escape.

This pattern is especially common in trauma and drug addiction, where opioids or sedatives become coping mechanisms for both pain and dysregulation.

Emotional Trauma and Addiction

Emotional trauma, such as abandonment, humiliation, chronic invalidation, or loneliness, is one of the most overlooked contributors to addiction. Emotional trauma disrupts attachment, creates deep shame, and erodes a sense of belonging.

Individuals often turn to substances to soothe:

shame

attachment wounds

fear of abandonment

emotional emptiness

chronic loneliness

Emotional trauma is one of the strongest predictors of unresolved trauma and addiction in adulthood.

Trauma and Addiction Recovery

Healing requires restoring safety, connection, and nervous system regulation. Effective trauma and addiction recovery integrates several key components:

1. Trauma-Informed Therapy

EMDR, Somatic Experiencing, Trauma-Focused CBT, and parts work help process traumatic memory and release stored stress.

2. Attachment-Based Therapy

Healing requires co-regulation. The therapeutic alliance (Siegel, Porges, Brown & Elliott) becomes a corrective emotional experience that rebuilds secure functioning.

3. Somatic and Body-Based Healing

Grounding, breathwork, yoga, and body awareness help reconnect with the body safely. Trauma is stored physically and must often be released somatically.

4. Mindfulness and Regulation Practices

Mindfulness helps build tolerance for internal experience and reduces urges to escape through substances.

5. Group and Community Support

One of the strongest healing factors in addiction and trauma recovery is belonging. Groups offer co-regulation, understanding, and the reduction of shame.

6. Medication Support (When Appropriate)

Medication can help stabilize mood, reduce trauma symptoms, or support early sobriety.

7. Safe Relationships

Healing trauma requires relational experiences where a person feels seen, known, and safe. Co-regulation is the antidote to trauma.

8. Lifestyle Practices

Sleep, nutrition, routine, movement, and nervous system hygiene support long-term resilience.

Addiction as Adaptation, Healing as Reconnection

The connection between trauma and addiction is undeniable. Addiction is not simply about pleasure or poor choices; it is often a survival adaptation to unbearable internal states caused by trauma. Healing requires compassion, safety, and relational support, not shame.

Recovery becomes possible when individuals experience co-regulation, process trauma, rebuild attachment security, and learn new ways to feel safe in their bodies and relationships.

Whether the trauma was emotional, physical, or rooted in early childhood, healing is always possible.

References and Influences

The concepts in this article draw from leading research and clinical work in trauma, addiction, attachment theory, and interpersonal neurobiology.

Trauma and the Nervous System

Bessel van der Kolk, MD

The Body Keeps the Score. Foundational work on how trauma affects the brain, body, and long-term regulation.

Peter Levine, PhD

Somatic Experiencing and the physiology of trauma responses.

Stephen Porges, PhD

Polyvagal Theory, highlighting the role of safety, co-regulation, and autonomic states.

Bruce Perry, MD, PhD

Neurosequential Model and developmental trauma research.

Attachment Theory and Trauma

John Bowlby & Mary Ainsworth

Foundational attachment theory and early relational models.

Dan Siegel, MD

Interpersonal neurobiology and the role of co-regulation in healing trauma.

Mary Main & Erik Hesse

Adult Attachment Interview and disorganized attachment research.

Patricia Crittenden, PhD

Dynamic-Maturational Model (DMM) and trauma-related attachment adaptations.

Trauma and Addiction

Gabor Maté, MD

Work on trauma, emotional loss, and addiction (In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts).

Philip J. Flores, PhD

Addiction as an Attachment Disorder. Core text linking insecure attachment and substance use.

ACE Study (Felitti et al., 1998)

Adverse Childhood Experiences research showing dose-dependent increases in addiction risk.

De Rick & Vanheule (2007)

High prevalence of disorganized attachment in inpatient addiction settings.

Schindler, A. (2019)

Meta-analyses on insecure attachment and substance use disorders.

PTSD and Complex Trauma

Judith Herman, MD

Trauma and Recovery. Framework for PTSD, CPTSD, and relational healing.

Onno van der Hart & Ellert Nijenhuis

Structural dissociation and personality fragmentation in trauma.

Clinical Models Supporting Trauma and Addiction Recovery

Daniel P. Brown & David Elliott

Ideal Parent Figure method and attachment repair.

Sue Johnson, EdD

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for relational trauma and bonding.

Stan Tatkin, PsyD

PACT model and secure-functioning relational principles.

Group Healing and Co-Regulation

G. Alan Marlatt, PhD

Relapse Prevention and the emotional regulation functions of substance use.

Bruce Alexander, PhD

Rat Park studies demonstrating the role of social connection in addiction outcomes.